The People We Left Behind: How Closing A Dangerous Border Camp Adds To Inequities

![]()

From her bedroom window, the 19-year-old transgender woman can see the site of the makeshift migrant camp in Matamoros that she fled months earlier, fearing for her safety.

Sanchez said she escaped Honduras in February 2020 after strangers beat her and left her for dead because of her gender identity. She spent the next eight months at the makeshift camp in Matamoros, but fled after other Central American migrants harassed and assaulted her and her transgender friends, telling them they would end up “dead in the river,” she recalled.

Sanchez never doubted her decision to leave until earlier this month, when President Joe Biden’s administration allowed nearly all of the 700 migrants at the camp to cross into the United States as part of a broader rollback of the MPP program, also known as “remain in Mexico.”

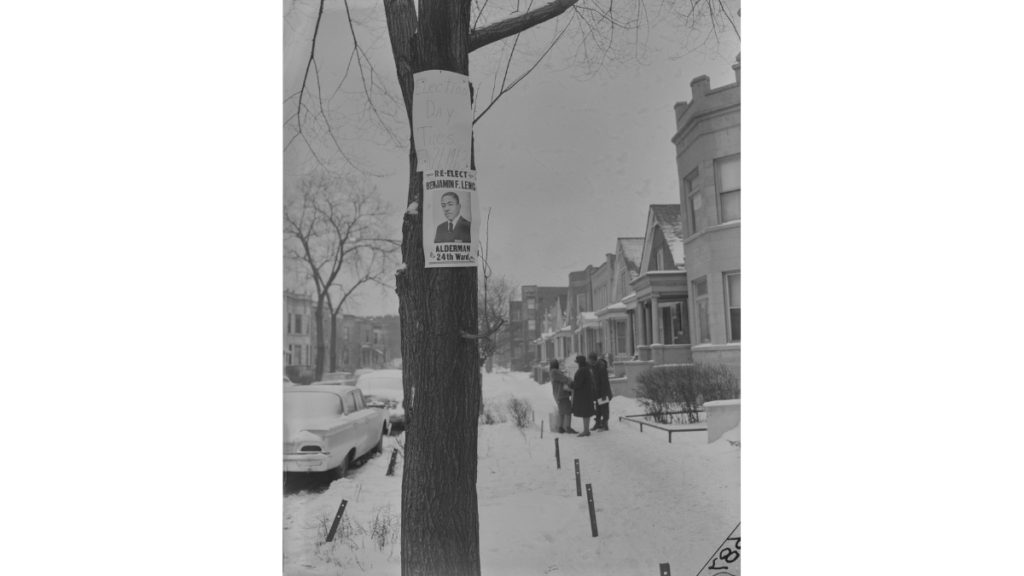

The closed-down migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico, on Feb. 24.

Credit:

Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica

Over a little more than a week, the fetid camp, which lacked running water and had sparked public health and safety concerns, was emptied in collaboration with the United Nations, a first at the U.S. border. The tents that had cluttered the Matamoros riverbank across from Brownsville, the southernmost point of the border between Texas and Mexico, were gone.

Advocates praised Biden for moving to eliminate one of the most visceral symbols of U.S. immigration policies under Trump. The camp had become notorious for the miserable conditions endured by migrants, drawing international attention as a U.S.- sanctioned refugee settlement.

But in closing the camp, the Biden administration strayed from its own guidelines to prioritize vulnerable migrants like Sanchez who have pending court cases, essentially allowing some in the camp to skip the line. Many migrants whose asylum cases had already been denied or who otherwise didn’t qualify for entrance were allowed into the U.S. to be processed, stoking confusion about who gets in and who doesn’t.

Department of Homeland Security officials said admissions from the camp were based on “urgent humanitarian concerns” and in consideration of keeping families together.

But officials involved in emptying the Matamoros camp, who were not authorized to speak publicly, said pressure in the U.S. and Mexico also factored into the decision to prioritize migrants from the camp. Last month’s record freeze in Texas and Northern Mexico added to alarm about conditions.

Sanchez and her housemates feel they are being punished for having sought a safer place to live. Had they stayed at the camp, they would be in the U.S. already, but now they are forced to wait.

“We didn’t leave the camp because we wanted to,” Sanchez said. “We had to.”

She is among tens of thousands of migrants in urgent situations who are so far left out.

“The distinction between who qualifies for relief and who doesn’t is pretty arbitrary,” said Jodi Goodwin, an immigration lawyer in the Rio Grande Valley who works on MPP cases. “It’s a huge, messy problem for the Biden administration.”

“Too Much Chaos”

About 40,000 migrants, a majority of those sent back across the border under the MPP program, have already been denied asylum or otherwise had their cases terminated, according to federal statistics. Only a tiny number have been approved for protection; the rest are still pending. Typically, after a judge rejects an asylum petition in the U.S., migrants are required to return to their home countries.

Many rejected migrants remain in Mexican border cities under perilous situations, hoping for another opportunity under Biden. His administration has not said if it will offer migrants with closed cases a second chance at asking for asylum. Goodwin and other lawyers said many claims were wrongly dismissed.

Trump made immigration a cornerstone of his campaign for office and his presidency, arguing that under previous administrations the U.S. had been too lenient and that regulations should be tightened to prevent immigrants from entering the country.

During his own presidential campaign, Biden noted that Trump was the first U.S. president to make asylum seekers wait in another country. He promised to undo some Trump-era immigration policies, including MPP, saying they were inhumane.

“That’s never happened before in America,” Biden said during a presidential debate last year. “They’re sitting in squalor on the other side of the river.”

The Biden administration halted the MPP program and in February began the process of allowing into the U.S. the 25,000 migrants with pending court cases. About 2,200 of those migrants have been admitted so far, including almost everyone from the Matamoros camp, according to the U.N.

They will now be allowed to live in the U.S. while they await hearings in civil immigration courts that have an average backlog of more than two years, according to federal statistics.

U.N. and U.S. officials said migrants with open cases are being processed as quickly as possible, emphasizing that those who have waited the longest and are most vulnerable should be permitted to enter first.

“The Matamoros camp became a visible symbol of a much larger problem,” said Yael Schacher, a historian who serves as a legal advocate at the global organization Refugees International. “But this is just a tiny, very visible population of a much larger group that is in many cases as vulnerable or more so.”

Newly confirmed Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has urged patience as the administration reconstructs a “dismantled” immigration system.

Biden officials have said that, under Trump, the U.S. decimated avenues to seek asylum, including returning unaccompanied migrant children without legal protections, and cut foreign aid that had been intended to improve conditions in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. The administration has promised reforms such as shortening the amount of time it takes to adjudicate asylum claims, but has not yet provided specifics.

“We have had to rebuild the entire system,” Mayorkas said Tuesday in a statement. “As difficult as the border situation is now, we are addressing it.”

Since taking office, Biden has grappled with an influx of migrants fleeing desperate conditions and hoping that the U.S. immigration system will be more welcoming under a new administration. In February, U.S. Border Patrol agents apprehended more than 19,200 migrants with their families, about 9,450 unaccompanied children and nearly 71,600 single adults, according to federal statistics released last week. The total of just more than 100,000 migrants was a 28% increase over January and the highest monthly number since June 2019.

Mayorkas said Tuesday that the U.S. is “on pace to encounter more individuals on the southwest border than we have in the last 20 years,” in part because of worsening conditions in Central America. A decision by the Biden administration to stop automatically expelling migrant children under a public health order invoked by Trump last March also resulted in an increase of unaccompanied minors entering the U.S.

That has forced the opening of extra facilities and left children in poorly equipped Border Patrol detention centers, which are intended for adults, for longer than the law allows. On March 13, Biden announced that he was deploying the Federal Emergency Management Agency to the border to help care for unaccompanied children.

Mayorkas and other federal officials have said that the border remains closed while the Biden administration tries to reconstruct legal avenues for those seeking protection.

“It’s going to take time,” said DHS spokesperson Sarah Peck. “In the meantime, the border is not open, and people should not make the journey to reach it.”

The confusion stemming from the camp’s closure has added to uncertainty about how the Biden administration is more broadly handling immigration cases involving migrants at the border.

Outside of MPP, the Biden administration is rejecting nearly all migrant adults and some families under the public health order from last March, which invoked COVID-19 as a reason for turning them away. At the same time, the government is allowing some newly arrived migrant families to enter in south Texas, pointing to a lack of shelter space because of new regulations in Mexico.

“Now it’s a bit of being at the right place at the right time,” said Savitri Arvey, a researcher on migration at the University of Texas at Austin. “That causes panic and misinformation.”

As the Matamoros camp was dismantled, new arrivals pitched tents outside of the park where it had stood. Asylum seekers in Tijuana, Mexico, across the border from San Diego, began forming their own camp at that border crossing, hoping to encounter a similarly speedy process. The Tijuana camp has grown to as many 1,500 people since mid-February, representatives from legal advocacy organizations have said. DHS officials warned that such tactics wouldn’t help.

“Physical presence at the U.S. border has not and will not be a means for gaining access to this phased program to address the Migrant Protection Protocols,” agency officials said in a statement to ProPublica and the Texas Tribune.

Charlene D’Cruz, an attorney with Lawyers for Good Government who works on MPP cases in the Rio Grande Valley, said the conditions in the Matamoros camp were on par with some of the worst refugee settlements she had witnessed in Greece. But D’Cruz said that prioritizing the camp without offering solutions to the larger number of people suffering in Mexico after being returned under MPP is political “tap dancing.”

“There’s too much chaos in an already very chaotic system,” D’Cruz said. “We need more transparency about what’s going to happen next and who is going to be included.”

Left Behind

Dinora Cruz doesn’t understand how U.S. authorities don’t see her as vulnerable or in need of protection.

Cruz, who was returned to Matamoros under the MPP program in 2019, said she pleaded her case to an immigration judge. She explained that gang members had sexually assaulted her twice in Honduras after extorting her for protection money for the convenience store she ran.

Once, she said, gangs broke into her house, firing a bullet that scraped her finger, leaving a deep, jagged scar. After a second attack on the street, she filed a police report with Honduran authorities. They noted in the report that the assault had left her with “serious psychological damage.”

She could no longer pay the extortion money and lost her business.

“The gangs threatened that if I did not give them money, then I would never see my kids again,” she told U.S. authorities at the border, according to her processing paperwork.

Without a lawyer, Cruz said, she struggled to complete her asylum application in English and articulate in court why she qualified. She said the immigration judge told her that she hadn’t provided enough proof and rejected her case in January 2020, just before the pandemic shuttered such courts.

Many migrants still waiting to enter the U.S. arrived at the border shortly after Trump’s MPP policy began in early 2019. Many of their cases were denied in tent courts that were not open to the public. Advocates denounced the legal proceedings, which included mass hearings through video conferencing with poor translation, according to lawyers.

Ariana Sawyer, a researcher with Human Rights Watch, likened the hearings to “kangaroo courts.” She said many migrants’ claims were not properly adjudicated. Of the more than 71,000 migrants returned to Mexico under the MPP program, less than 8% had legal representation. The U.S. government does not provide attorneys to immigrants in such civil deportation proceedings.

Many waited across the border in dangerous conditions. More than 1,500 were killed, kidnapped or assaulted in Mexico while waiting for their court dates, according to tallies by Human Rights First and other international groups.

After the program was implemented, judges granted asylum or other forms of U.S. protection to only about 650 migrants in the MPP program, according to federal data analyzed by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

The Trump administration also made multiple changes to immigration courts, which according to the Migration Policy Institute, a think tank in Washington, D.C, reduced the asylum grant rate to the lowest in decades.

The measures created a broader crisis at the border.

“The Matamoros camp ultimately contained only a tiny fraction of those asylum seekers subjected to this cruel border policy,” Sawyer said.

Because a U.S. judge had dismissed Cruz’s asylum claim, Mexican authorities also revoked her permission to stay and work there lawfully while she awaited her fate in a Texas court. Now she and her two boys, 9 and 10, are living in Mexico illegally. The children have not attended school for more than a year.

Cruz said she is too afraid to return to Honduras. Another woman sent back under the MPP program, who works at a clinic for migrants outside of the Matamoros tent camp, allowed Cruz to stay for free in her rented room.

But the woman has a pending asylum case under MPP and has been told by the U.N. that she will soon be allowed to enter the U.S. under the Biden’s administration’s rollback of the program.

Without a job and with no other options for housing, Cruz doesn’t know how she will take care of her boys once the woman leaves.

Desperation Remains

The Rev. Juan Sierra, who oversees a migrant shelter in Matamoros, stood outside of the tent camp earlier this month as the U.N. began processing migrants to enter the U.S. Sierra was relieved that they would no longer be living in unsafe conditions, but he feared that the city’s two available shelters would not be able to accommodate the remaining migrants and those who continue to arrive daily.

“The camp isn’t suitable anymore for people to live,” Sierra said. “But if they take away the camp, we don’t have enough space.”

Sierra said his facility can house only about 120 migrants under pandemic protocols. The city’s second shelter is much smaller.

He said the U.S. and Mexico must come up with a clear plan for processing migrants seeking asylum and other protections. Otherwise, Sierra said, migrants could resort to entering the country in increasingly dangerous ways.

“Migrants are going to get criminal groups to go to the U.S., and people are going to die,” Sierra said. “Hopefully both governments come up with a humanitarian solution.”

Rhonda Fleischer, a migration program specialist at UNICEF, which is involved with the dismantling of the MPP program, said migrants are fleeing not only endemic gang violence and poverty but the aftermath of two deadly hurricanes in Central America last year. Many are also searching for employment after months of severe COVID-19 shutdowns obliterated the few available jobs in their countries.

“There is nothing for people anymore,” Fleischer said. “I hear the call for people to wait, that the U.S. is working to find solutions for people who genuinely need protection.”

Nonetheless, she said, “there are families in situations in Central America in which they are in life-or-death circumstances.”

In Matamoros, the tent camp is gone, but the desperation remains.

Sanchez, still living in her crowded apartment with other gay and transgender migrants, checked Facebook for updates on her closest friend, Natasha Mayorquin, who also had a pending case and was let into the U.S. last week as part of the MPP rollback.

The sprawling settlement is no longer visible out Sanchez’s window. At night, she instead looks out and sees the lights of Brownsville. She thinks about her friend, now on her way to North Carolina.

“I feel pretty alone,” she said.

Like thousands of migrants across the border, she clings to hope that she’ll be next.

The People We Left Behind: How Closing A Dangerous Border Camp Adds To Inequities

Responses